As a history researcher, I am interested in studying the course of the Persian Empire from its beginnings to its present state. I will also try to trace its effect on our present world, especially on Egypt and the Arab world. In a series of articles, I will deal with the appearance of the Persian Empire and discuss its effect on the Arab world. This article will be dedicated to the rise and fall of the Persian Empire.

The Achaemenid Empire

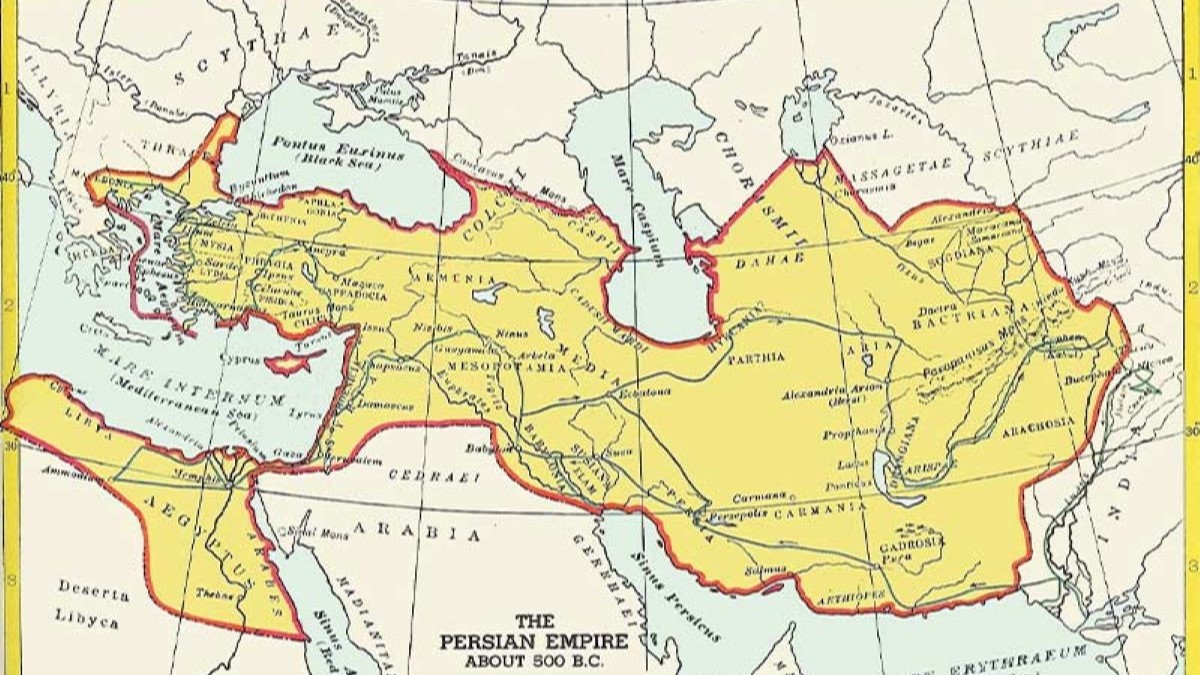

The Achaemenid Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire, was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. The empire, based in modern Iran, was the largest in history at that time, covering a total area of 5.5 million square kilometres (2.1 million sq mi). The empire stretched from the Balkans and Egypt in the west, West Asia as a base, Central Asia to the northeast, and the Indus Valley to the southeast.

Around 850 BC the original nomadic people who began the empire called themselves the Parsa and their constantly shifting territory Parsua, for the most part, was localized around Persis. The name "Persia" is a Greek and Latin pronunciation of the native word referring to the country of the people originating from Persis.

The Persian Empire started as a collection of semi-nomadic tribes who raised sheep, goats and cattle on the Iranian plateau in the southwestern part of the Iranian Plateau around the 7th century BC.

From Persia, Cyrus the Great—the leader of one such tribe—began to defeat nearby kingdoms, including Media, Lydia and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, joining them under one rule. Thus, he marked the formal establishment of a new imperial policy under the Achaemenid dynasty., also known as the Persian Empire, in 550 B.C.

In modern times, the Achaemenid Empire has been recognised for its successful implementation of a centralized bureaucratic administration, its multicultural policies, the construction of complex infrastructure such as road systems and an organized postal system, the use of official languages throughout its territory, and the development of civil services, including a large professional army. Its progress inspired the implementation of similar patterns of rule by a variety of later empires.

Origin of the Achaemenid Dynasty

The Achaemenid Empire was founded by nomadic Persians. The Persians were an Iranian people who arrived in what is now Iran around 1000 BC and settled in an area that included northwestern Iran, the Zagros Mountains, and Persis, along with the indigenous Elamites. The Persians were originally nomadic pastoralists on the western Iranian plateau. The Achaemenid Empire may not have been the first Iranian empire, as the Medes, another group of Iranian people, may have founded a short-lived empire when they played a major role in overthrowing the Assyrians.

The Achaemenids were initially rulers of the Elamite city of Anshan near the modern city of Mervdasht; the title "king of Anshan" was taken from the earlier Elamite title "king of Susa and Anshan".

There are conflicting accounts of the identities of the earliest kings of Anshan. According to the Cyrus Cylinder, the kings of Anshan were Teshepis, Cyrus I, Cambyses I, and Cyrus II, also known as Cyrus the Great, who founded the empire. The later Behistun inscription, written by Darius the Great, claims that Tychepis was the son of Achaemenes and that Darius was also descended from Tychepis through a different line, but no earlier texts mention Achaemenes. In the Histories, Herodotus writes that Cyrus the Great was the son of Cambyses I and Mandane of Media, daughter of Astyages, king of the Median Empire.

Revolt against the Median Empire

Cyrus revolted against the Median Empire in 553 BC, and in 550 BC he succeeded in defeating the Medes, capturing Astyages, and capturing the Median capital of Ecbatana. Once he had taken control of Ecbatana, Cyrus proclaimed himself Astyages' successor and assumed control of the entire empire. By inheriting Astyages' empire, he also inherited the Medes' territorial conflicts with both Lydia and the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Conquest of Lydia

King Croesus of Lydia sought to take advantage of the new international situation by advancing into what had been Median territory in Asia Minor. Cyrus led a counterattack that not only defeated Croesus' armies but also led to the capture of Sardis and the fall of the Lydian kingdom in 546 BC. Cyrus put Pectes in charge of collecting tribute in Lydia and left, but once Cyrus had left, Pectes incited a rebellion against Cyrus. Cyrus sent the Median general Mazares to deal with the rebellion, and Pectes was captured. Mazares, and after his death, Harpagus, proceeded to reduce all the cities that had participated in the rebellion. It took about four years in total to subdue Lydia.

When the power in Ecbatana passed from the Medes to the Persians, many tributaries of the Median empire believed that their status had changed and revolted against Cyrus. This forced Cyrus to wage wars against Bactria and the nomadic Saka people of Central Asia. During these wars, Cyrus established several garrison cities in Central Asia, including Cyropolis.

Conquest of Babylon

In October 539 BC, Cyrus won a battle against the Babylonians at Opis, then captured Sippar without a fight before finally capturing the city of Babylon on October 12, where the Babylonian king Nabonidus was captured. Upon capturing the city, Cyrus portrayed himself in propaganda as restoring the divine order that had been disrupted by Nabonidus, who had promoted the worship of Sin instead of Marduk, and as restoring the heritage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by comparing himself to the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.

The Hebrew Bible also unreservedly praises Cyrus for his actions in conquering Babylon, referring to him as the Messiah of the Lord. He is credited with liberating the people of Judah from their exile and commissioning the rebuilding of much of Jerusalem, including the Second Temple.

Defeat of the Massagetae in Central Asia

In 530 BC, Cyrus died, presumably while on a military expedition against the Massagetae in Central Asia. He was succeeded by his eldest son Cambyses II, while his younger son Bardiya received a large territory in Central Asia.

Subjugation of Phoenicia and Cyprus

By 525 BC, Cambyses had successfully subjugated Phoenicia and Cyprus and was making preparations to invade Egypt with the newly created Persian navy.

Defeat of Egypt

Pharaoh Amasis II died in 526 and was succeeded by Psamtik III, resulting in the defection of key Egyptian allies to the Persians. Psamtik positioned his army at Pelusium in the Nile Delta. He was soundly defeated by the Persians in the Battle of Pelusium before fleeing to Memphis, where the Persians defeated him and took him prisoner. After attempting a failed revolt, Psamtik III promptly committed suicide.

Expansion in Africa

After the conquest of Egypt, the Libyans and Greeks of Cyrene and Barqa in present-day eastern Libya (Cyrene) surrendered to Cenbyses and sent tribute without a fight. Cambyses then planned to invade Carthage, the Ammonite oasis, and Ethiopia.

Herodotus claims that the naval invasion of Carthage was cancelled because the Phoenicians, who formed a large part of Cambyses' fleet, refused to take up arms against their people, but modern historians doubt whether an invasion of Carthage was ever planned.

Cambyses, however, devoted his efforts to the other two campaigns, to improve the empire's strategic position in Africa by conquering the kingdom of Meroe and taking up strategic positions in the western oases. To this end, he established a garrison at Elephantine consisting mainly of Jewish soldiers, who remained stationed at Elephantine throughout Cambyses' reign.

The conquests of Ammon and Ethiopia themselves were failures. Herodotus claims that the invasion of Ethiopia was a failure due to Cambyses' madness and lack of supplies for his men, but archaeological evidence suggests that the campaign was not a failure, and the fortress at the Second Cataract of the Nile, on the border between Egypt and Kush, remained in use throughout the Achaemenid period.

Surrender of Macedonia

Since the Macedonian king Amyntas I had surrendered his country to the Persians in about 512-511, the Macedonians and Persians were no strangers either. The subjugation of Macedonia was part of the Persian military operations initiated by Darius the Great (521-486) in 513.

Invasion of the Balkans

After massive preparations, a huge Achaemenid army invaded the Balkans and attempted to defeat the European Scythians roaming north of the Danube. Darius’s army subjugated many Thracian peoples, and almost all the other areas touching the European part of the Black Sea, such as parts of modern Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, before returning to Asia Minor. Darius left one of his generals in Europe, Megabazus, who was tasked with conquests in the Balkans. The Persian forces subjugated gold-rich Thrace and the coastal Greek cities, defeating and conquering the powerful Paeonians. Finally, Megabazus sent envoys to Amyntas, demanding that he accept Persian dominance, which the Macedonians did. The Balkans provided many soldiers for the multi-ethnic Achaemenid army. Many married into the Macedonian and Persian elite, such as the Persian official Bubares who married Amyntas' daughter, Gygaia. The family ties that the Macedonian rulers Amyntas and Alexander enjoyed with Bubares ensured their good relations with the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes I, also known as Xerxes the Great.

The Height of the Persian Empire

By the 5th century BC, Persian kings either ruled or were vassals over territories that included not only the entire Persian plateau and all the lands formerly subject to the Assyrian Empire (Mesopotamia, the Levant, Cyprus, and Egypt), but also beyond that, all of Anatolia and Armenia, as well as the southern Caucasus and parts of the northern Caucasus, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Bulgaria, Paonia, Thrace, and Macedonia to the north and west, most of the Black Sea coastal areas, parts of Central Asia as far as the Aral Sea, the Oxus and Jaxartes to the north and northeast, the Hindu Kush Mountains and the western Indus River basin (corresponding to modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) to the far east, parts of northern Arabia to the south, parts of eastern Libya (Syriac) to the southwest, and parts of Oman, China, and the United Arab Emirates.

Decline of the Persian Empire

Artaxerxes III was succeeded by Artaxerxes IV Arses, who before he could act was also poisoned by Bagoas. Bagoas is further said to have killed not only all Arses' children but many of the other princes of the land. Bagoas then placed Darius III, a nephew of Artaxerxes IV, on the throne. Darius III, previously the Satrap of Armenia, personally forced Bagoas to swallow poison. In 334 BC, when Darius was just succeeding in subduing Egypt again, Alexander and his battle-hardened troops invaded Asia Minor.

Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) defeated the Persian armies at Granicus (334 BC), followed by Issus (333 BC), and lastly at Gaugamela (331 BC). Afterwards, he marched on Susa and Persepolis which surrendered in early 330 BC. From Persepolis, Alexander headed north to Pasargadae, where he visited the tomb of Cyrus, the man whom he had heard of from the Cyropaedia.

In the ensuing chaos created by Alexander's invasion of Persia, Cyrus's tomb was broken into and most of its luxuries were looted. When Alexander reached the tomb, he was horrified by how it had been treated, and questioned the Magi, putting them on trial. By some accounts, Alexander's decision to put the Magi on trial was more an attempt to undermine their influence and display his power than a show of concern for Cyrus's tomb. Regardless, Alexander the Great ordered Aristobulus to improve the tomb's condition and restore its interior, showing respect for Cyrus. From there he headed to Ecbatana, where Darius III had sought refuge.

Darius III was taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman. As Alexander approached, Bessus had his men murder Darius III and then declared himself Darius' successor, Artaxerxes V, before retreating into Central Asia leaving Darius' body on the road to delay Alexander, who brought it to Persepolis for an honourable funeral. Bessus would then create a coalition of his forces, to create an army to defend against Alexander. Before Bessus could fully unite with his confederates in the eastern part of the empire, Alexander, fearing the danger of Bessus gaining control, found him, put him on trial in a Persian court under his control, and ordered his execution in a "cruel and barbarous manner."

Alexander generally kept the original Achaemenid administrative structure, leading some scholars to dub him "the last of the Achaemenids". Upon Alexander's death in 323 BC, his empire was divided among his generals, the Diadochi, resulting in several smaller states. The largest of these, which held sway over the Iranian plateau, was the Seleucid Empire, ruled by Alexander's general Seleucus I Nicator. Native Iranian rule would be restored by the Parthians of northeastern Iran over the 2nd century BC through the Parthian Empire.

Muslim Conquest of Persia

The Islamic Conquest of Persia, also called the Islamic Conquest of Iran, the Arab Conquest of Persia, or the Arab Conquest of Iran, was a major military campaign undertaken by the Rashidun Caliphate between 632 and 654. As part of the early Islamic conquests, which began under Muhammad in 622, it led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire and the eventual decline of Zoroastrianism, which had been prevalent throughout Persia as the official religion of the country.

The persecution of Zoroastrians by early Muslims during and after this conflict led many of them to flee eastward to India, where they were granted asylum by various kings. While the Arabian Peninsula was experiencing the rise of Islam in the 7th century, Persia was struggling with unprecedented levels of political, social, economic, and military weakness; the Sasanian army had largely exhausted itself in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. After the execution of the Sasanian Shah Khosrow II in 628, internal political stability in Persia began to deteriorate rapidly. Ten new claimants to the throne were installed over the next four years. Soon after, Persia was further devastated by the Sassanid Interregnum, a large-scale civil war that began in 628 and resulted in the decentralization of government by 632.

Amidst the turmoil in Persia, the first Muslim invasion of Sassanid territory occurred in 633, when a Muslim army conquered parts of Ashuristan, the Sassanid political and economic centre in Mesopotamia. Later, the regional Muslim army commander Khalid ibn al-Walid was transferred to oversee the Muslim conquest of the Levant, and with the Muslim army increasingly focused on the Byzantine Empire, the Sassanid army reconquered the newly conquered Mesopotamian territories.

The second Rashidun invasion began in 636, led by Saad ibn Abi Waqqas when a decisive victory at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah permanently ended all Sassanid control to the west of modern Iran. For the next six years, the Zagros Mountains, a natural barrier, marked the political boundary between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sassanid Empire.

In 642, Umar ibn al-Khattab, eight years after becoming the second caliph of Islam, ordered a full-scale invasion of the rest of the Sassanid Empire. Directing the war from Medina in Arabia, Umar’s rapid conquest of Persia in a series of coordinated, multi-pronged attacks became his greatest triumph, contributing to his reputation as a great military and political strategist. However, in 644, he was assassinated by the Persian craftsman Abu Lu’lu’a Firuz, who was captured by the Rashidun Caliphs’ soldiers and brought to Arabia as a slave.

Some Iranian historians have defended their predecessors by using Arabic sources to demonstrate that “the Iranians, contrary to the claims of some historians, fought the invading Arabs for a long time and with great force.” By 651, most of the urban centres in Iran, except for the provinces along the Caspian Sea (i.e., Tabaristan and Transoxiana), were under Muslim control. Many areas fought the invaders; although the Rashidun army established control over most of the country, many cities revolted against them by killing their Arab governors or attacking their garrisons.

Eventually, military reinforcements succeeded in suppressing the Iranian rebellions and establishing complete control. The conversion of the Iranians to Islam was gradual, the result of various incentives over centuries, although some Iranians never converted, and there is widespread evidence of the systematic burning of Zoroastrian and other pre-Islamic scriptures and the execution of Zoroastrian priests, especially in areas that served as centres of resistance. Islam became the dominant religion in Iran by the late Middle Ages; the majority of Iranians were Sunni Muslims until the Safavids forcibly converted Iran to Shia Islam in the 18th century.

Umayyad era

After the fall of the Sasanian Empire in 651, the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate adopted many Persian customs, particularly in administrative practices and court manners. The Arab provincial governors were often Persianized Arameans or ethnic Persians; notably, Persian remained the language of official business within the caliphate until Arabic gradually replaced it toward the end of the seventh century, with the first minting in Damascus occurring in 692. The new Islamic coins were based on Sasanian and Byzantine designs, and the Pahlavi script was replaced with the Arabic alphabet on the coinage.

During the Umayyad Caliphate, the Arab conquerors imposed Arabic as the primary language throughout their empire. Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, who was dissatisfied with the prevalence of the Persian language in the Divan, ordered that the official language of the conquered lands be replaced by Arabic, sometimes enforcing this change by force.

In the 7th century, many non-Arabs, including Persians, entered Islam and were recognized as mawali (clients). However, they were treated as second-class citizens by the ruling Arab elite until the end of the Umayyad Caliphate. At this time, Islam was often seen as tied to Arab ethnic identity, which required a formal association with an Arab tribe alongside the adoption of the mawali client status. The late Umayyads' half-hearted attempts to tolerate non-Arab Muslims and Shias proved unsuccessful in quelling unrest among these groups.

Despite the expansion of the Arabs, not all of Iran fell under their control. The region of Daylam remained under the Daylamites, while Tabaristan was governed by the Dabuyids and Paduspanids. The area around Mount Damavand was under the control of the Masmughans of Damavand. Although the Arabs invaded these regions multiple times, they achieved no decisive victories due to the challenging terrain. The most notable ruler of the Dabuyids, Farrukhan the Great (r. 712–728), managed to maintain his territory during a long struggle against the Arab general Yazid ibn al-Muhallab. Yazid was ultimately defeated by a combined Dailamite-Dabuyid army and was forced to retreat from Tabaristan.

The death of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 743 triggered a civil war in the Islamic world. The Abbasid Caliphate sent Abu Muslim to Khorasan initially as a propagandist and later to lead a revolt on their behalf. He captured Merv, defeating the Umayyad governor Nasr ibn Sayyar, and became the de facto Abbasid governor of Khurasan. During this time, the Dabuyid ruler Khurshid declared independence from the Umayyads but was soon compelled to recognize Abbasid authority. In 750, Abu Muslim led the Abbasid army to victory against the Umayyads at the Battle of the Zab. He later stormed Damascus, the capital of the Umayyad caliphate, later that same year.

Autonomous Iranian Dynasties

The Abbasid army was primarily made up of Khorasanians and led by an Iranian general named Abu Muslim Khorasani. It included both Iranian and Arab elements, benefiting from support from both groups. The Abbasids successfully overthrew the Umayyads in 750. According to Amir Arjomand, the Abbasid Revolution signified the end of the Arab empire and the beginning of a more inclusive, multi-ethnic state in the Middle East.

One of the first actions the Abbasids took after seizing power from the Umayyads was to relocate the empire's capital from Damascus in the Levant to Iraq. This region had been significantly influenced by Persian history and culture, and the relocation was part of the Persian mawali's demand for reduced Arab dominance in the empire. The city of Baghdad was established along the Tigris River in 762 to serve as the new Abbasid capital.

The Abbasids introduced the position of vizier, similar to the Barmakids, which functioned as a "vice-caliph" or second-in-command. Over time, this meant that many Abbasid caliphs assumed more ceremonial roles, while the vizier held real power. A new Persian bureaucracy began to replace the old Arab aristocracy, reshaping the administration and highlighting the differences between the new dynasty and the Umayyads.

By the 9th century, Abbasid control started to weaken as regional leaders emerged, challenging the central authority of the Abbasid caliphate. The Abbasid caliphs began enlisting mamluks, Turkic-speaking warriors, who had migrated from Central Asia into Transoxiana and served as slave warriors from as early as the 9th century. Consequently, the actual power of the Abbasid caliphs diminished, turning them into mere religious figureheads while the mamluks ruled.

During this period, a revolt by native Zoroastrians, known as the Khurramites, erupted against oppressive Arab rule. This movement was led by a Persian freedom fighter, Babak Khorramdin. Babak's rebellion, advocating for the revival of Iranian political glory, originated in Azerbaijan in northwestern Iran. The revolt spread through western and central Iran and lasted over twenty years, ultimately ending when Babak was betrayed by Afshin, a senior general of the Abbasid Caliphate.

As the power of the Abbasid caliphs declined, various dynasties rose in different parts of Iran, some wielding significant influence. Among the most notable were the Tahirids in Khorasan (821–873), the Saffarids in Sistan (861–1003, continuing as Maliks of Sistan until 1537), and the Samanids (819–1005), who initially ruled from Bukhara and extended their control from central Iran to Pakistan.

By the early 10th century, the Abbasids nearly lost control of the emerging Persian faction known as the Buyid dynasty (934–1062). Since much of the Abbasid administration was already Persian, the Buyids were able to quietly assume real power in Baghdad. They were eventually defeated in the mid-11th century by the Seljuq Turks, who continued to influence the Abbasids while publicly pledging allegiance to them. This arrangement led to a power dynamic in Baghdad where the Abbasids held power only in name until the Mongol invasion in 1258, which sacked the city and effectively ended the Abbasid dynasty.

During the Abbasid period, there was a significant enfranchisement of the mawali, and political conceptions shifted from being primarily Arab to being recognized as a Muslim empire. Around 930, a requirement was enacted that mandated all bureaucrats of the empire to be Muslims.

Islamic Golden Age

Islamization in Iran was a gradual process through which the majority of the population adopted Islam. Richard Bulliet's "conversion curve" suggests that during the Arab-centric Umayyad period, only about 10% of Iranians converted to Islam. However, with the onset of the Abbasid period, which saw a combination of Persian and Arab rulers, the proportion of Muslims in the population began to increase. By the mid-9th century, the Muslim population was approximately 40%, and this number rose to nearly 90% by the end of the 11th century. Seyyed Hossein Nasr argues that the rapid increase in conversions was facilitated by the Persian heritage of the rulers.

Despite adopting the religion of their conquerors, Persians worked to protect and revitalize their distinct language and culture over the centuries in a process known as Persianization. This effort involved both Arabs and Turks.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, non-Arab subjects of the Ummah initiated a movement called Shu'ubiyyah in response to the privileged status enjoyed by Arabs. While many of its proponents were Persian, references to Egyptians, Berbers, and Aramaeans are also noted. Grounded in Islamic principles of racial and national equality, the movement focused on preserving Persian culture and identity within a Muslim framework.

The Samanid dynasty played a crucial role in reviving Persian culture, and the first significant Persian poet after the arrival of Islam, Rudaki, emerged during this period, receiving acclaim from the Samanid kings. The subsequent Ghaznawids, who were of non-Iranian Turkic origin, also contributed significantly to the revival of Persian culture.

The Islamization of Iran brought profound transformations in the cultural, scientific, and political structures of society. This period marked a flourishing of Persian literature, philosophy, medicine, and art, which became key components of the emerging Muslim civilization. Situated at the crossroads of major cultural trade routes and with a rich heritage spanning thousands of years, Persia significantly contributed to what is now recognized as the "Islamic Golden Age." During this time, numerous scholars and scientists made substantial advances in technology, science, and medicine, influencing the rise of European science during the Renaissance.

Some of the most important scholars in nearly all Islamic sects and schools of thought were Persian or lived in Iran. This includes notable Hadith collectors from both Shia and Sunni traditions, such as Shaikh Saduq, Shaikh Kulainy, Hakim al-Nishaburi, Imam Muslim, and Imam Bukhari. Prominent theologians like Shaykh Tusi and Imam Ghazali, as well as leading physicians, astronomers, mathematicians, and philosophers like Avicenna and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, also emerged during this era. The greatest figures in Sufism, including Rumi and Abdul-Qadir Gilani, were also part of this rich intellectual tradition.

Persianate states and dynasties (977–1219)

In 977, Sabuktigin, a Turkic governor of the Samanids, conquered Ghazna (present-day Afghanistan) and established the Ghaznavid dynasty, which lasted until 1186. The Ghaznavid Empire expanded by taking all Samanid territories south of the Amu Darya in the last decade of the 10th century and eventually occupied parts of Eastern Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern India.

The Ghaznavids are credited with introducing Islam to predominantly Hindu India. This invasion began around 1000 under the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud and continued for several years. However, they struggled to maintain control, especially after Mahmud died in 1030. By 1040, the Seljuqs had taken over the Ghaznavid lands in Iran.

The Seljuqs, like the Ghaznavids, were of Turkic origin and Persianate in culture. They gradually conquered Iran throughout the 11th century. Their roots lay in the Turcoman tribal confederations of Central Asia, marking the rise of Turkic power in the Middle East. The Seljuqs established a Sunni Muslim rule across parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to the 14th centuries, forming what is known as the Great Seljuq Empire. This empire stretched from Anatolia in the west to western Afghanistan in the east and the western borders of present-day China in the northeast. The Seljuq Empire was also a target of the First Crusade. Today, they are regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Western Turks—today's inhabitants of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan—and are remembered as significant patrons of Persian culture, art, literature, and language.

The dynasty's founder, Tughril Beg, directed his army against the Ghaznavids in Khorasan, moving south and then west, conquering various cities along the way without looting them. In 1055, the Caliph in Baghdad honoured Tughril Beg with robes, gifts, and the title of King of the East. Under Tughril Beg's successor, Malik Shah (1072–1092), Iran experienced a cultural and scientific renaissance, significantly aided by his brilliant Iranian vizier, Nizam al-Mulk. They established an observatory where Omar Khayyám conducted much of his research for a new calendar, and built religious schools in major towns. They also brought Abu Hamid Ghazali, one of the great Islamic theologians, and other eminent scholars to the Seljuq capital in Baghdad, encouraging and supporting their work.

When Malik Shah I died in 1092, his empire fractured as his brother and four sons fought over territory. Kilij Arslan I succeeded Malik Shah I in Anatolia and founded the Sultanate of Rûm, while his brother Tutush I took over Syria. In Persia, Malik Shah I was succeeded by his son Mahmud I, whose reign was contested by his brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Muhammad I in Baghdad, and Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan. As Seljuq's power declined in Iran, other dynasties began to rise, including a resurgent Abbasid caliphate and the Khwarezmshahs. The Khwarezmid Empire was a Sunni Muslim Persianate dynasty of East Turkic origin that ruled in Central Asia. Originally, vassals of the Seljuqs, they seized the opportunity presented by the Seljuq decline to expand into Iran. In 1194, Khwarezmshah Ala ad-Din Tekish defeated the Seljuq sultan Toghrul III in battle, leading to the collapse of the Seljuq Empire in Iran. By this time, only the Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia remained of the former Seljuq Empire.

During their reign, the Seljuqs also faced a serious internal threat from the Nizari Ismailis, a secret sect with headquarters at Alamut Castle between Rasht and Tehran. They controlled the surrounding area for over 150 years and occasionally sent adherents to strengthen their influence by assassinating important officials. Some theories regarding the etymology of the word "assassin" stem from these killers.

In the early 13th century, parts of northwestern Iran were conquered by the Kingdom of Georgia, led by Tamar the Great.

Mongol invasion (1219–1221)

The Khwarazmian dynasty lasted only a few decades before the arrival of the Mongols. Under Genghis Khan, the Mongol Empire rapidly expanded in several directions. By 1218, it bordered Khwarezm, which was ruled by Ala ad-Din Muhammad (1200–1220). Like Genghis, Muhammad sought to expand his territory and had already gained control over most of Iran. He declared himself shah and sought formal recognition from the Abbasid caliph Al-Nasir. When the caliph rejected his claim, Ala ad-Din Muhammad appointed one of his nobles as caliph and made an unsuccessful attempt to depose Al-Nasir.

The Mongol invasion of Iran began in 1219 after two diplomatic missions sent by Genghis Khan to Khwarezm were massacred. Between 1220 and 1221, cities like Bukhara, Samarkand, Herat, Tus, and Nishapur were destroyed, and their entire populations were slaughtered. The Khwarezm-Shah fled and ultimately died on an island off the Caspian coast. During the invasion of Transoxiana in 1219, Genghis Khan employed a Chinese catapult unit alongside the main Mongol force, using it again in 1220 in Transoxania. The Chinese may have utilized these catapults to launch gunpowder bombs, already in their possession at that time.

While Genghis Khan was conquering Transoxania and Persia, several Chinese individuals skilled in gunpowder served in his army. Entire regiments composed of Chinese troops operated bomb-hurling trebuchets during the invasion of Iran. Historians suggest that the Mongol invasion introduced Chinese gunpowder weapons to Central Asia, including a type of mortar known as the huochong. Subsequent literature from the region depicted gunpowder weapons resembling those of China.

Destruction under the Mongols

Before he died in 1227, Genghis Khan had reached western Azerbaijan, pillaging and burning many cities after entering Iran from the northeast.

The Mongol invasion was largely disastrous for the Iranians. Although the Mongol invaders eventually converted to Islam and adopted aspects of Iranian culture, their devastation in Iran and other regions of the Islamic heartland—particularly in the historical Khorasan region, mostly located in Central Asia—marked a significant turning point for the area. Much of the six centuries of Islamic scholarship, culture, and infrastructure was lost as the invaders levelled cities, burned libraries, and, in some cases, replaced mosques with Buddhist temples.

The Mongols killed many Iranian civilians. The destruction of the qanat irrigation systems in northeastern Iran disrupted the pattern of continuous settlements, leading to many abandoned towns that once thrived on irrigation and agriculture.

Ilkhanate (1256–1335)

After Genghis Khan’s death, Iran was ruled by several Mongol commanders. Genghis's grandson, Hulagu Khan, was tasked with the westward expansion of Mongol dominance. However, by the time he took power, the Mongol Empire had already fragmented into different factions. Arriving with an army, he established himself in the region and founded the Ilkhanate, a breakaway state from the Mongol Empire, which would rule Iran for the next eighty years and gradually adopt Persian culture.

Hulagu Khan captured Baghdad in 1258 and executed the last Abbasid caliph. His westward advance, however, was halted by the Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut in Palestine in 1260. Hulagu's campaigns against Muslim territories also provoked Berke, the khan of the Golden Horde and a convert to Islam. The conflict between Hulagu and Berke illustrated the weakening unity of the Mongol Empire.

During the rule of Hulagu's great-grandson, Ghazan (1295–1304), Islam was established as the state religion of the Ilkhanate. Ghazan, alongside his renowned Iranian vizier, Rashid al-Din, initiated a brief economic revival in Iran. The Mongols reduced taxes for artisans, promoted agriculture, rebuilt and enhanced irrigation systems, and improved the safety of trade routes. Consequently, commerce flourished.

Trade items from India, China, and Iran traversed the Asian steppes, enriching Iranian culture. For instance, Iranians developed a new style of painting that blended solid, two-dimensional Mesopotamian techniques with light brush strokes and other motifs characteristic of Chinese art. However, after Ghazan's nephew Abu Said died in 1335, the Ilkhanate descended into civil war, fragmenting into several petty dynasties, most notably the Jalayirids, Muzaffarids, Sarbadars, and Kartids.

The mid-14th-century Black Death resulted in the death of about 30% of the country’s population.

Sunnism and Shiism in pre-Safavid Iran

Before the rise of the Safavid Empire, Sunni Islam was the dominant religion in Iran, comprising around 90% of the population. According to Mortaza Motahhari, the majority of Iranian scholars and the general populace remained Sunni until the advent of the Safavid era. However, this Sunni dominance did not mean that Shia Islam was absent from Iran. Many influential Shia scholars, as well as the authors of The Four Books of Shia, were Iranian.

The prevalence of Sunni Islam characterized Iran's religious history during the first nine centuries of Islam. Nonetheless, there were some exceptions, such as the Zaydīs of Tabaristan, the Buyids, the Kakuyids, the reign of Sultan Muhammad Khudabandah (r. 1304–1316), and the Sarbedaran.

During these nine centuries, Shia inclinations existed among many Sunnis in the region. Original Imami Shiism and Zaydī Shiism had a presence in certain areas. During this time, Shia communities were influenced by centres such as Kufah, Baghdad, Najaf, and Hillah. Shiism was particularly dominant in places like Tabaristan, Qom, Kashan, Avaj, and Sabzevar, where Shia and Sunni populations often coexisted.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, the Fatimids sent Ismaili missionaries (Da'is) to Iran and other Muslim regions. When the Ismailis split into two sects, the Nizaris established a stronghold in Iran. Hassan-i Sabbah captured the fortress of Alamut in 1090 AD, which the Nizaris maintained until a Mongol raid in 1256.

Following the Mongol invasion and the decline of the Abbasid caliphate, Sunni authority weakened. They not only lost the caliphate but also their status as the official madhhab. This decline opened the door for Shia Islam, which, at the time, did not yet have a strong centre in Iran. Several local Shia dynasties, such as the Sarbadars, emerged during this period.

The most significant change occurred in the early 16th century when Ismail I established the Safavid dynasty and implemented a religious policy recognizing Shia Islam as the official religion of the Safavid Empire. The establishment of Shia Islam as the state religion has directly influenced the modern identity of Iran as an officially Shi'ite state.

Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

Iran remained divided until the arrival of Timur, a Turco-Mongol from the Timurid dynasty. Like its predecessors, the Timurid Empire was part of the Persianate world. After establishing a power base in Transoxiana, Timur invaded Iran in 1381 and eventually conquered most of the region. His campaigns were known for their brutality, resulting in the slaughter of many people and the destruction of several cities.

Timur's regime was marked by tyranny and bloodshed, but it also included Iranians in administrative roles and promoted architecture and poetry. His successors, the Timurids, maintained control over most of Iran until 1452 when they lost a significant portion of it to the Black Sheep Turkmen. The Black Sheep Turkmen were later conquered by the White Sheep Turkmen under Uzun Hasan in 1468, who and his successors dominated Iran until the rise of the Safavids.

During the Timurid era, the Sufi poet Hafez gained widespread popularity, and his divan was compiled and copied extensively. Sufis often faced persecution from orthodox Muslims who deemed their teachings blasphemous. To navigate this hostility, Sufism developed a symbolic language rich in metaphors to obscure provocative philosophical ideas. Hafez concealed his own Sufi beliefs while using this secretive language perfected over hundreds of years in his poetry. His work inspired the poet Jami, whose popularity also spread throughout the Persianate world.

Kara Koyunlu

The Kara Koyunlu were a Turkmen tribal federation that ruled over northwestern Iran and the surrounding areas from 1374 to 1468 CE. They expanded their conquests to Baghdad; however, internal conflicts, defeats by the Timurids, rebellions by Armenians in response to their persecution, and failed struggles with the Aq Qoyunlu ultimately led to their demise.

Ak Koyunlu

The Aq Qoyunlu, also a Turkmen group, were led by the Bayandur tribe and were a federation of Sunni Muslims who ruled over most of Iran and large parts of the surrounding areas from 1378 to 1501 CE. The Aq Qoyunlu emerged when Timur granted them control of Diyar Bakr, located in present-day Turkey. They faced challenges from their rival Oghuz Turks, the Kara Koyunlu. While the Aq Qoyunlu successfully defeated the Kara Koyunlu, their struggle with the rising Safavid dynasty eventually led to their downfall.

Safavid Empire (1501–1736)

The Safavid dynasty was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties and is often regarded as the beginning of modern Persian history. They governed one of the greatest Persian empires following the Muslim conquest of Persia and established the Twelver school of Shi'a Islam as the official religion of their empire, marking a crucial turning point in Muslim history. The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722, with a brief restoration from 1729 to 1736. At their height, they controlled all of modern Iran, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, most of Georgia, the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Safavid Iran was one of the Islamic "gunpowder empires," alongside its neighbours, the Ottoman Empire and the Mughal Empire.

The dynasty was founded by Ismāil, who styled himself Shah Ismāil I. Revered by his Qizilbāsh followers, Ismāil invaded Shirvan to avenge the death of his father, Shaykh Haydar, who had been killed during a siege of Derbent in Dagestan. After capturing Tabriz in July 1501, he proclaimed himself the Shah of Iran, minted coins in his name and declared Shi'ism the official religion of his domain.

Although initially ruling only Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan, the Safavids won the struggle for power in Persia that had been ongoing for nearly a century among various dynasties and political entities following the fragmentation of the Kara Koyunlu and the Aq Qoyunlu. A year after his victory in Tabriz, Ismāil proclaimed most of Persia as his domain and quickly conquered and unified Iran under his rule. The Safavid Empire rapidly expanded its territory, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, parts of Georgia, Mesopotamia (Iraq), Kuwait, Syria, Dagestan, large areas of what is now Afghanistan, parts of Turkmenistan, and significant portions of Anatolia, laying the foundation for its multi-ethnic character, particularly evident in the Caucasus and its peoples.

Tahmasp I, the son and successor of Ismāil I, conducted multiple invasions of the Caucasus, regions that had been integrated into the Safavid Empire. He initiated the trend of deporting and relocating hundreds of thousands of Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians to Iran's heartland. Initially, these groups were placed in royal harems, royal guards, and other minor sections of the empire. To diminish the power of the Qizilbāsh, the military tribal elite of the empire, Tahmasp sought to create a new layer in Iranian society. According to the Encyclopædia Iranica, Tahmasp's challenge centred around the Qizilbāsh, who believed that their proximity to the Safavid family would ensure spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement.

Shah Abbas I and his successors significantly expanded upon Tahmasp's policies. During his reign alone, Abbas deported around 200,000 Georgians, 300,000 Armenians, and 100,000–150,000 Circassians to Iran, further establishing a new layer within Iranian society. This systematic disorganization of the Qizilbāsh, carried out under Abbas's orders, led to the replacement of their power with that of the Caucasian ghulams. These new Caucasian individuals, often converted to Shi'ism based on their roles, would be loyal solely to the Shah, unlike the Qizilbāsh. Other Caucasian migrants were deployed across various functions in the empire, including in the harem, regular military, craftsmanship, and agriculture. This system of utilizing Caucasian subjects persisted until the fall of the Qajar dynasty.

The greatest of the Safavid monarchs, Shah Abbas I the Great, ruled from 1587 to 1629, coming to power at the age of 16. His early reign focused on military expansion. He first targeted the Uzbeks, recapturing Herat and Mashhad in 1598, territories lost by his predecessor, Mohammad Khodabanda, during the Ottoman-Safavid War (1578–1590). Following this, Abbas turned his attention to the Ottomans, the Safavids' archrivals, successfully recapturing Baghdad, eastern Iraq, and the Caucasian provinces by 1618.

Between 1616 and 1618, following disobedience from his loyal Georgian subjects, Teimuraz I and Luarsab II, Abbas launched a punitive campaign in Georgia that devastated Kakheti and Tbilisi, resulting in the capture of between 130,000 and 200,000 Georgians, who were taken to mainland Iran. His new army, significantly improved by the arrival of Robert Shirley and his brothers after the first diplomatic mission to Europe, achieved a decisive victory over the Ottomans in the 1603–1618 conflict, surpassing them in military strength. Abbas also dislodged the Portuguese from Bahrain in 1602 and Hormuz in 1622, with assistance from the English navy.

He expanded commercial ties with the Dutch East India Company and established strong connections with European royal houses, building on the earlier Habsburg-Persian alliance initiated by Ismail I. This allowed Abbas to reduce reliance on the Qizilbash for military support, enabling him to centralize control. Although the Safavid dynasty had been established under Shah Ismail I, it became a major world power during Abbas I’s reign, competing with the Ottoman Empire on equal footing. He also promoted tourism in Iran, leading to a revival of Persian architecture, with Isfahan as a notable example.

Aside from Abbas the Great, Shah Ismail I, Shah Tahmasp I, and Shah Abbas II, many later Safavid rulers were ineffective, often distracted by leisure activities such as indulging in women and alcohol. The end of Abbas II's reign in 1666 marked the beginning of the Safavid decline. Despite facing dwindling revenues and military threats, many later shahs maintained lavish lifestyles, with Shah Soltan Hosain (1694–1722) particularly notorious for his love of wine and disinterest in governance.

As the country declined, its frontiers were repeatedly raided. In 1722, Mir Wais Khan, a Ghilzai Pashtun chieftain, led a rebellion in Kandahar, defeating the Safavid army commanded by Gurgin Khan, a Georgian governor. That same year, Peter the Great of Imperial Russia initiated the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many Caucasian territories of Iran, including Derbent, Shaki, Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran, and Astrabad. Amid this chaos, Mahmud, Mir Wais's son, marched across eastern Iran, besieging and capturing Isfahan, where he proclaimed himself 'Shah' of Persia. Meanwhile, Persia's rivals, the Ottomans and Russians, seized the opportunity to expand their territories. These events effectively marked the end of the Safavid dynasty. In 1724, under the Treaty of Constantinople, the Ottomans and Russians agreed to divide the newly conquered Iranian territories between themselves.

The Rise of Islamic Persian Empire

Political and religious conflict soon erupted among the early Muslims, and the Persians later used this conflict to realize the dreams of the Persian Empire. The beginnings of the conflict between the early Muslims appeared when Ali ibn Abi Talib took power in the Islamic world. On the other hand, the Arabs invaded the Persian state between 632 and 654, and thus the Persians found in the power struggle between the Muslims a means to re-establish the lost Persian Empire.

Ali ibn Abi Talib (in Arabic: عليّ بن أبي طالب; c. 600–661 CE) was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was the fourth Rashidun Caliph who ruled from 656 to 661 CE, as well as the first Shiite Imam. Ali the Younger was born to Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib and Fatima bint Asad and was raised by his older cousin Muhammad and was one of the first to accept his teachings.

Ali played a pivotal role in the early years of Islam when Muslims were severely persecuted in Mecca. After the migration to Medina in 622, Muhammad gave his daughter Fatima to Ali in marriage and swore a brotherly covenant with him. Ali served as Muhammad's secretary and deputy during this period and was the standard-bearer of his army.

There are many sayings of Muhammad praising Ali, the most controversial of which is his statement in 632 at Ghadir Khumm, "Whoever I am his master, this Ali is his master." The interpretation of the polysemous Arabic word "mawla" is disputed: for Shia Muslims, Muhammad granted Ali his religious and political authority, while Sunni Muslims view this as a mere statement of friendship and understanding.

When Muhammad died in the same year, a group of Muslims met in Ali's absence and appointed Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) as their leader. While the appointment of Abu Bakr was met with little resistance in Medina, the Banu Hashim and some companions of Muhammad soon gathered in protest at Ali's house. Among them were Zubayr and Muhammad's uncle Abbas. These protestors held Ali to be the rightful successor to Muhammad. Among others, al-Tabari reports that Umar then led an armed mob to Ali's residence and threatened to set the house on fire if Ali and his supporters did not pledge their allegiance to Abu Bakr.

The scene soon grew violent, but the mob retreated after Ali's wife, Fatima, pleaded with them. Abu Bakr later placed a successful boycott on the Banu Hashim, who eventually abandoned their support for Ali. Most likely, Ali himself did not pledge his allegiance to Abu Bakr until Fatima died within six months of her father, Muhammad.

In Shia sources, the death and miscarriage of the young Fatima are attributed to an attack on her house to subdue Ali by the order of Abu Bakr. Sunnis categorically reject these reports, but there is evidence in their early sources that a mob entered Fatima's house by force and arrested Ali, an incident that Abu Bakr regretted on his deathbed. Likely a political move to weaken the Banu Hashim, Abu Bakr had earlier confiscated from Fatima the rich lands of Fadak, which she considered her inheritance from her father. The confiscation of Fadak is often justified in Sunni sources with a hadith about prophetic inheritance, the authenticity of which has been doubted partly because it contradicts Quranic injunctions.

Ali later renounced his claims to leadership and resigned from public life under Abu Bakr and his successor, Umar (r. 634–644). Although he was occasionally consulted, the conflicts between Ali and the first two caliphs were exemplified by his refusal to follow their practices. This refusal cost Ali the caliphate in favour of Uthman (r. 644–656), who was appointed Umar's successor by an electoral council. Ali was also highly critical of Uthman, who was widely accused of nepotism and corruption. However, Ali repeatedly mediated between the caliph and regional opponents angry at his policies.

After Uthman's assassination in June 656, Ali was elected caliph in Medina. He immediately faced two separate rebellions, both ostensibly to avenge Uthman: the triumvirate of Talha and al-Zubayr, both companions of Muhammad, and his widow Aisha seized Basra in Iraq but were defeated by Ali at the Battle of the Camel in 656. Elsewhere, Muawiyah, whom Ali had just removed from the governorship of Syria, fought against Ali at the inconclusive Battle of Siffin in 657, which ended in a failed arbitration that alienated some of Ali's supporters. These formed the Kharijites, who later terrorized the public and were crushed by Ali at the Battle of Nahrawan in 658. Ali was assassinated in 661 by the dissident Kharijite Ibn Muljam, paving the way for Muawiyah to seize power and establish the Umayyad Caliphate.

Ali is revered and respected for his courage, honesty, absolute devotion to Islam, generosity, and equal treatment of all Muslims. He thus became to his admirers a model of uncorrupted Islam and pre-Islamic chivalry. Sunni Muslims consider him the last of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs, while Shia Muslims revere him as their first Imam, the legitimate religious and political successor to Muhammad. Ali is said to be second only to Muhammad in Shia Islamic culture. The shrine of Ali in Najaf, Iraq, is a major Shia pilgrimage site. Ali’s legacy has been collected and studied in many books, the most famous of which is Nahjul Balagha.

The Emergence of Shiism

The political dispute between the Rashidun Caliphs over who was most entitled to rule the lands of the Muslims developed into what is known as Shiism or Shiite Islam after the death of Ali ibn Abi Talib.

Shiite Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. Shiites believe that the Prophet Muhammad appointed Ali ibn Abi Talib (656-661 CE) as his successor as Imam, especially in Ghadir Khumm. Still, after the death of the Prophet, Ali was prevented from succeeding the caliphate as leader of the Muslims as a result of the choice made by some of Muhammad's other companions at Saqifah. This view is primarily in contrast to the view of Sunni Islam, whose followers believe that Muhammad did not appoint a caliph before his death and consider Abu Bakr, who was appointed caliph by a group of Muhammad's other companions at Saqifah, to be the first legitimate caliph after Muhammad (632-634 CE).

The Shia Muslim belief that Ali was the appointed successor to Muhammad as the spiritual and political leader of Islam later evolved into the concept of Imamate, the idea that certain descendants of Muhammad, the Ahl al-Bayt, are legitimate rulers or imams through the lineage of Ali and his sons Hasan and Husayn, who Shia Muslims believe hold special spiritual and political authority over the Muslim community.

Subsequent events such as the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali at the Battle of Karbala (680 CE) influenced the development of Shia Islam, contributing to the formation of a distinct religious sect with its rituals and shared collective memory.

Shia Islam is followed by 10–15% of all Muslims. Although there are many Shia sub-sects in the Islamic world, Twelver Shia is the largest and most influential, comprising approximately 85% of all Shia Muslims. Other religions include Ismailism, Zaydism, Alawism, and Aleviism. Shia Muslims constitute the majority of the population in three countries across the Islamic world: Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan. There are also large Shia communities in Lebanon, Kuwait, Turkey, Yemen, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and the Indian subcontinent. Iran is the only country in the world where Shia Islam forms the basis of both its laws and its system of government.

Al-Hasan ibn Ali

After Ali's death, his eldest son Al-Hasan became the leader of the Muslims in Kufa. After a series of skirmishes between the Muslims of Kufa and Mu'awiyah's army, Al-Hasan ibn Ali agreed to cede the caliphate to Mu'awiyah and maintain peace among the Muslims on certain conditions: he would not publicly curse Ali, for example during prayer; Mu'awiyah would not use tax money for his own needs; there would be peace, and Al-Hasan's followers would be granted security and rights; Mu'awiyah would never adopt the title of Amir al-Mu'minin ("Commander of the Faithful"); Mu'awiyah would not nominate any successor.

Al-Hasan then retired to Medina, where he was poisoned in 670 CE by his wife Ja'dah bint al-Ash'ath, after being secretly approached by Mu'awiyah who wanted to transfer the caliphate to his son Yazid and saw Al-Hasan as an obstacle.

Husayn ibn Ali, Ali's younger son and Al-Hasan's brother, initially resisted calls to lead the Muslims against Mu'awiyah and restore the caliphate. In 680 CE, Mu'awiyah died and transferred the caliphate to his son Yazid, breaking the treaty with Al-Hasan ibn Ali. Yazid asked Husayn to swear allegiance (bay'ah) to him.

Ali's faction expected the caliphate to return to the Alid dynasty after Mu'awiyah's death, so they saw this as a betrayal of the peace treaty, so Husayn refused this demand for allegiance. There was a wave of support in Kufa for Husayn to return there and assume his position as caliph and imam, so Husayn gathered his family and followers in the city and set out for Kufa. On his way to Kufa, Husayn was intercepted by an army of Yazid's men, which included people from Kufa, near Karbala; rather than surrender, Husayn and his followers chose to fight. Husayn and approximately 72 of his family and followers were killed in the Battle of Karbala, and Husayn's head was given to Yazid in Damascus.

The Shi'a community regards Husayn ibn Ali as a martyr and considers him an imam of the Ahl al-Bayt. The Battle of Karbala and the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali are often cited as the final split between the Shi'a and Sunni sects in Islam. Husayn is the last imam after Ali recognized by all branches of Shi'a Islam. The martyrdom of Husayn and his followers is commemorated on the Day of Ashura, which falls on the tenth day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar.